The Lion King, Robocop, Aladdin: How Not to Do a Movie Remake

With the recent release of Disney’s live-action remake of their iconic animated film The Lion King, it seems like now would be an appropriate time to discuss the concept and execution of cinematic remakes in general. It should be noted that isn’t a “should people even try to attempt a remake of an original” piece because the answer really is: it depends. Contrary to what we’ve said about the waning quality of Disney’s live-action adaptation of animated films, we don’t actually hate the idea of a remake.

In fact, some of our favourite films have been remakes that have outdone and even surpassed their previous counterpart. That being said, the number of times that has occurred are rare and far between. Most of them just end up becoming soulless cash cows doing their very best to cash in on a property’s nostalgia points. The results were mediocre at best and utterly insulting at their very worst.

So with that said, we decided to give our two cents on how not to screw up cinematic remakes of previous properties. It’s worth taking into account that there is a key difference between remakes and reboots. Reboots are films made to either jumpstart, restart or ret-con existing film franchises and properties. So while 2016’s Ghostbusters bears the same name as the original, it is not considered a remake but rather an attempt at a new starting point in the franchise.

The same way Bumblebee is seen as a soft reboot of Bay’s Transformers films. Reboots have no obligation to recreate or maintain the narrative integrity of previous films in their timeline. Remakes, on the other hand, are seen to be modern updates of the identical, or near-identical, stories told before. We all good? Okay, let’s jump in.

Careless Changes

Great remakes are rarely shot-for-shot recreations of the films’ previous properties. Even the most faithful rendition of an older film will undoubtedly have a change or two made, whether they be in the form of aesthetics or additional narrative threads. An excellent example of a remake done right would be John Carpenter’s The Thing which was a remake of 1951’s The Thing from Another World. Both follow a rather similar plot, an alien lifeform crashing on Earth and attacking a research facility.

Both aliens have regenerative abilities and are capable of changing their shape. Where the departure begins is in the way Carpenter uses the alien’s ambiguous nature to heighten suspense and slowly but surely turn what could have been a by-the-numbers alien invasion film into a chilling sci-fi psychological thriller. Unlike the original, there’s no true form given to the creature that stalks the crew of Antarctic base.

Carpenter also understood that the themes of foreign invasion through outlandish, camp creature designs would not have been as effective as an insidious infiltrator in human guise. The remake was made during the paranoia and fear of the Cold War with Russians and Americans rooting out potential spies and traitors in their very own neighbourhoods.

So to have the alien reflect the fears of the time not only made the film feel more relevant, it complemented the original. Similarly with Steven Spielberg’s 2005 remake of 1953’s War of the Worlds. He didn’t change the premise but merely made some key choices to better appeal to a post-9/11 America.

While a film like Independence Day, made in 1996, was made to be an exemplar of American exceptionalism and optimism, War of the Worlds was meant to be seen as a stark rebuttal to that belief. The otherworldly terror inflicted upon suburban Americans was foreign, alien and devastating with little to no explanation as to why these horrors were happening. It was made to comment on the nation’s growing fear of the “other” out there, lurking and waiting to destroy your way of life. The changes made in these two films had all the relevance of the culture they inhabited while still retaining a healthy reverence for the story in a culture of another time. These changes had purpose and meaning.

Sadly remakes like Carpenter’s The Thing, Spielberg’s War of the Worlds are the exception, not the rule. Over the years, major studios have attempted to cash in the nostalgic quality of existing film properties. They’ve created remakes of popular films that have changes that are frankly stupid. When a filmmaker sets his or her heart to remaking a classic film, it should stem from a place of, dare I say, evangelical wonder!

Their thought process should be “Wow what an amazing film that was and now I want to honour it by bringing it to a new audience in a way that speaks to them as much it spoke to me.” Most of the time, however, cinematic remakes are birth from a moronic premise of “People like old popular things and that made a lot of money…I like money so we make new old popular thing for people.”

Let’s take 2010’s The Karate Kid for example, arguably one of the most confusing remakes I’ve ever laid my eyes upon. Where do I even begin with this piece of shit? The original Karate Kid was set in Newark, New Jersey which followed the story of a kid named Daniel LaRusso learning to overcome a bully who uses an unethical form of Karate known as “Cobra Kai”. He seeks the wisdom of an elderly Karate master/maintenance man Mr Miyagi. Through patience and training, Daniel defeats the bully, gets the girl and learns important life lessons.

Is it the most radical concept ever put to screen? Probably not but it has a ton of heart and a message anyone can relate to. A remake should be fairly simple then, right? Apparently not seeing that for some jackass reason the remake is set in China! Wrong culture, you nitwits. Why did this change need to happen? This new location adds nothing unique to the plot. They couldn’t even be bothered to change the title of the film, out of fear that they might lose nostalgia points.

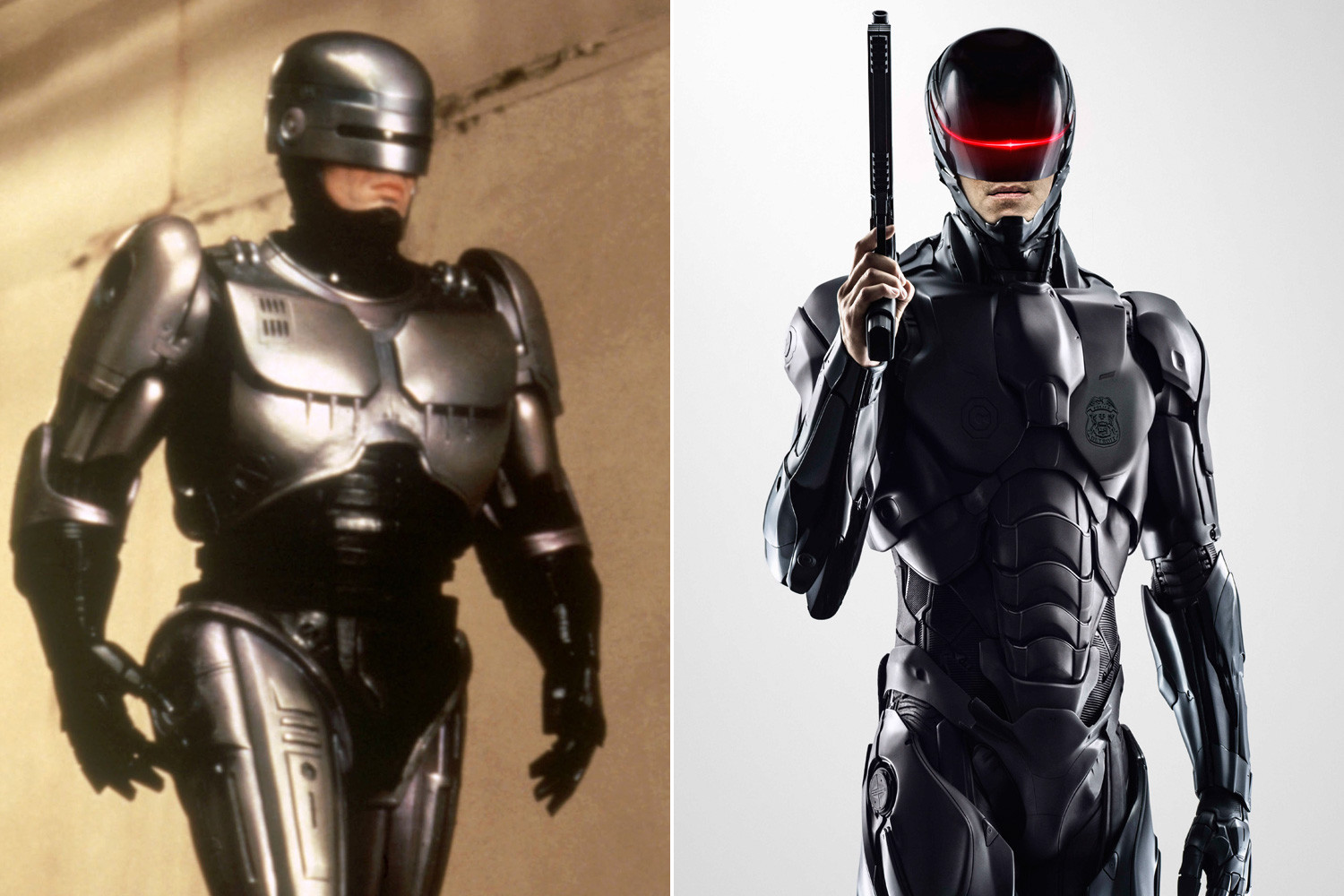

If you’re looking for a more contemporary screw-up, let’s discuss 2014’s Robocop remake. The original was a gritty R-rated critique of the intersection between the military-industrial complex and law enforcement. The film saw a noble cop by the name of Murphy have his limbs brutally blown off, one at a time by a gang of vicious criminals. A corrupt mega-corporation, Omni Consumer Products (OCP) uses this tragedy to transform him Murphy into a cold, efficient cyborg. Funnily enough, the remake attempts to mimic the original’s critique but this time without any hint of nuance or subtlety.

Hell, they pretty much just have Sam Jackson spell out the OCP’s evil intentions for all the world to see. The iconic and tragic torture and death of Murphy is now replaced with a car explosion. A decision that clearly indicates the studio has no idea what made the original Robocop so great! Murphy’s death wasn’t just an exercise in gratuitous violence. It was meant to make us question the necessity for authoritarian order in light of vicious criminal elements. It also served as both the catalyst of a physical and mental rebirth of Murphy into his new life as a powerful, mechanical fascist. All that context, however, is thrown out of the window in the name of earning that PG-13 rating…hurray.

Again, I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with remakes having changed or adding something new to an existing story. In fact, if there was absolutely no innovation in a remake, its existence should be called into question. That being said, filmmakers must understand that every alteration, amendment and addition made will significantly affect everything from character motivation to the overall structure and integrity of the story you’re trying to tell. A Butterfly Effect that if not taken into account could potentially ruin a remake. In the past, some of these changes have been warranted. Some of them were made in the name of diversity. Nowadays, A LOT of these changes are made for one reason alone: escalation.

Errant Escalations

There seems to be a prevailing philosophy in the film industry with regards to how bigger is better. Though it is not a completely flawed concept, it is a trap that studio executives and writers have fallen for time and time again. It has become a crutch for writers and directors to fall back upon. Allow me to illustrate this point using a recent remake of 90’s action classic Point Break.

The original 1991 film had a simple, dumb and just plain fun idea. Let’s make a rad FBI crime drama in which a loose cannon who goes by the name Johnny Utah infiltrates a group of thrill-seeking surfer criminals who rob banks to fund their escapades. With Utah growing ever closer to the group, he finds himself at a crossroads. Does he stay on the straight and narrow or does he ride the wave? The plot is pretty absurd but Keanu Reeves and Patrick Swayze’s charm along with plenty of fun action set pieces aids us in suspending our disbelief. It’s an enjoyable, campy B-grade bro film with lots of style and just enough substance. The 2015 remake, however, isn’t contented to be just that.

2015’s Point Break attempts to one-up the original in every department and ends up falling flat on its face. It isn’t enough for there to be a fun and campy plot about a guy called Johnny Utah surfing waves. Now there have to be these elaborate wingsuit sequences that didn’t need to be there. Unlike the wave-riding and sky-diving portions of the original Point Break, these scenes are noticeably devoid of any sort of meaningful joy and camaraderie.

Yes, the new sport setpieces are technically more high stakes but that’s only a single aspect of what made the original so great. Where was that amazing circle of trust that Utah made with the other divers as they plunged from the air? Say what you want about how dumb the original Point Break was but you can’t deny that Reeves’ Utah and Swayze’s Bodhi had a genuine connection. Oh, and we need to talk about the changes made to Bodhi in the 2015 version.

The original antagonist of the film, Bodhi had simple motivations and yet the performance Swayze gave elevated the character, making the man charming and likeable as he appealed to the daredevil side of Utah. Whereas 2015’s Bodhi is the exact opposite! His motivation is some convoluted eco-terrorist plot to disrupt capitalist structures and industries to achieve some sort of balance to save the world. There’s also a whole thing about him attempting to achieve his master’s goal of honouring the forces of nature. He’s pretty much budget Ra’s al Ghul from Batman Begins.

Why couldn’t he just be a criminal thrill-seeker trying to live life to the fullest? Why does he need some silly pseudo-spiritual horseshit backstory? This is a classic case of conflating convoluted motivations as character complexity. Nobody gives two shits about why he’s doing it if we can’t relate to him on a human level or if we’re not engaged with his charisma. Which by the way, the actor here has none. ZERO. The actor Edgar Ramirez constantly looks like his voice is putting himself to sleep!

The direction of the remake was clearly going for something more serious, self-important and meditative. The problem is, there’s no need here. The absurd nature of the original doesn’t need anymore escalation. Its charming camp doesn’t require a fresh, sophisticated revamp. This issue is rampant throughout Hollywood. Everything from Disney’s attempt to make Alice in Wonderland more “epic” to Ridley Scott’s rendition of Charles Heston’s Ten Commandments in Exodus: Gods and Kings.

Right, it’s clear as day as day that cinematic remakes aren’t going away anytime soon. To be fair, I get it. It makes sense to bank on cultural nostalgia because there’s already an existing fanbase ready to consume it. It’s certainly easier than trying to build a whole film franchise from the ground up. I merely ask that filmmakers remember these two rules when doing remakes of beloved film properties.

The first being to layout the entire structure of the previous film’s plot in a linear timeline, doing so will help put things into perspective. So before changing and adding things to a remake, consider the cause-and-effect to the overall story and character development. Secondly, filmmakers should take the time to understand what fans love about the original. Identify its strengths and disregard its weaknesses. We sincerely filmmakers will take our advice to heart lest we have history repeat itself again, each time worse than before.

The post The Lion King, Robocop, Aladdin: How Not to Do a Movie Remake appeared first on Lowyat.NET.

from Lowyat.NET https://ift.tt/2XOrAa7

Labels: Lowyat

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home